I finished reading this book quite some time ago - ummm, about two months ago. At the time, I was reading Torey Hayden's book One Child as well. Strangely, the books both revolve around a child who for one reason or another had been moved from one home to another after the loss of their mother. In Hayden's book, which is a true story, the young six year old girl was abused by her family and showed her distaste for the world by setting a neighborhood toddler on fire. The story told by Hayden, the little girl's teacher, is heartbreaking and uplifting at the same time. Slowly, Hayden was able to break through the barriers the little girl had surrounding herself to protect from all the horribleness in the world. She did not know love until she met this teacher.

Missing May by Cynthia Rylant is nothing like One Child because the young child in this story was able to pull from the inner love she remembered from her own mother (who died) while she was passed from family to family. Then, a miracle happened, and Summer went to live with May and Ob. The story unfolds after May has died and both Summer and Ob are trying to come to terms with May's absence. Like so many children in stressful situations, young Summer is worried that she has to put her grief on hold to help Ob cope with his. With the assitance Summer's quirky classmate Cletus, Summer and Ob find peace without May - knowing that she remains a part of their lives. Seen through the eyes of the young girl, the author helps us to realize that love does not have to come in shiny big boxes or cost any money - it can be in the form of an old trailer filled with whirlygigs and whatnots!

After finishing both books, I wondered what in the world made me think they were related at all. So I reread Missing May and found myself weeping at the fictional comments of young Summer, who had everything that Hayden's real-life child did not. Here are two paragraphs that show you what I mean:

I know I must have been loved like that, even if I can't remember it. I must have; otherwise, how could I even recognize love when I saw it that night between Ob and May? Before she dies, I know my mother must have loved to comb my shiny hair and rub that Johnson's baby lotion up and down my arms and wrap me up and hold me all night long. She must have know she wasn't going to live and she must have held me longer than any other mother might, so I'd have enough love in me to know what love was when I saw it or felt it again.

When she died and all her brothers and sisters passed me from house to house, nobody ever wanting to take care of me for long, I still had that lesson in love deep inside me and I didn't grow mean or hateful when nobody cared enough to make me their own little girl. My poor mother had left me enough love to go on until somebody did come along who'd want me. (p. 4)

Torey Hayden's child must not have had that reserve - or maybe when awful, awful things happen to you it is difficult to remember the good. At any rate, these books made me want to thank everyone who loves and cares for children who might not otherwise have love in their lives.

Also, just to set this post straight - this book was not depressing in the least - it was really very uplifting and funny.

Flusi Cat

Tuesday, July 31, 2007

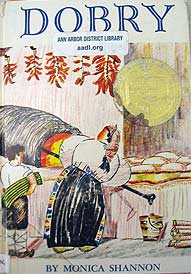

Dobry (1935 Winner)

When I issued the July challenge, I was already several tens of pages into this book. I did not know I would be cutting it so close (July 31) in trying to finish before the end of the month. I read the final words this morning on the bus heading in to work.

When I issued the July challenge, I was already several tens of pages into this book. I did not know I would be cutting it so close (July 31) in trying to finish before the end of the month. I read the final words this morning on the bus heading in to work.I chose this book more or less randomly. When one is planning to read all Newbery books sooner or later, there is no wrong selection. They all "count" toward the end goal (and I am nothing if not goal oriented).

Yet the two things that drew me to the book once it was in my hands were the title and the cover illustration. The book had no jacket-cover preview. I was left to discern what I could from its appearance.

To this former student of the Russian Language, Dobry meant "Good." That word, above the amateurishly drawn domestic scene promised a sweet tale about what is good in peasant life. In that regard, the book did not disappoint. It was, in fact, about the simple yet satisfying work and rites of the people in a Bulgarian village.

[spoilers below]

Surprisingly, Dobry turns out to be the protagonist's name. I don't know Bulgarian to know if it is also the word for "good," or if it is simply a name. The book gives us two years in Dobry's life. The first is when he's a boy of maybe 7-10 years. He helps around the house, relishes the outdoors, and displays a talent for art.

Surprisingly, Dobry turns out to be the protagonist's name. I don't know Bulgarian to know if it is also the word for "good," or if it is simply a name. The book gives us two years in Dobry's life. The first is when he's a boy of maybe 7-10 years. He helps around the house, relishes the outdoors, and displays a talent for art.The second section of the book takes place when Dobry is an adolescent. His artistic skills have blossomed into a rare gift the whole village recognizes.

What I found rewarding about the book were its accounts of everyday life in a mountain village before electricity or modern culture. Each chapter revealed something about how seasons were celebrated, traditions observed and relationships maintained.

Beyond that charming and no doubt rosified view, the book was not very good. It reminded me of the one Lois Lensky book I read, where very little happens and one is not given a reason to care about the characters. And ironically, the illustrations in this story about a budding artist, are bad. I can only guess they were supposed to look like folk art and have that unpolished composition. On more than one occasion, however, I could not tell what was happening in a photo until after I finished the chapter to which it corresponded.

Reading this book was like looking through a viewmaster. Each chapter was a different snapshot, and it didn't really matter where one began.

Hitty: Her First Hundred Years

This is a charming story in which a doll shares her adventures, which over the span of a hundred years have taken her around the globe. She starts life as a small, carved gift from a snowed-in peddler in Maine to the daughter of a whaler. Through circumstance, the family ends up on a whaling ship together and quite a long time passes before Hitty returns to America.

While the story is certainly dated by certain expressions and references to world religions and ethnicities, the point is very strongly made that worth cannot be gauged merely through appearances. Young and old, rich and poor alike are united in the desire to love and nurture little Hitty.

The Whipping Boy

The Whipping Boy by Sid Fleischman was illustrated by Peter Sis. This was a very quick read and full of mini-adventures that would probably entertain most children. The illustrations were in black and white and quite the match to the story. We have all probably heard the phrase "whipping boy" and while we knew what was meant by the words, I know I was not really sure how the terms came into use. The Phrase Finder provides some history of the term and traces it to the 15th and 16th centuries in England. It is interesting to note that the practice was NOT to use street urchins, but to select one of near-noble birth...this is contradicted by the story by Fleishhman.

So, on to the story: Jemmy was the orphaned son of a rat-catcher who lived in the sewers of the city before he was brought to the castle to serve as the whipping boy for Prince Brat, as he was not so lovingly referred to by his subjects. Each time the Prince did something wrong, Jemmy was whipped. Because the Prince was bored, he decided to run away and Jemmy was to go with him to serve as his man-servant. The two soon run into trouble and many fabulous characters as they navigate around the city hiding from the king's men who were searching for the Prince. As the two boys overcome many obstacles, they slowly become friends. They eventually make their way back to the palace where all is forgiven and the two boys remain friends and companions - with no more whippings!

In the author's note at the end of the book, Fleishman says, "History is alive with lunacies and injustices." I suppose that is why I spent six years of my life studying history with all of its insanity!

Flusi

PS. If you are a librarian (or even if you aren't I suppose), check out the YouTube post at my work related blog, LibrarysCat. It is a wonderful affirmation of what we, as librarians, should be doing to move the field into the 21st century! Also, this book post will be posted at my book blog Now that my required work blogging is done, I can concentrate more on reading!

So, on to the story: Jemmy was the orphaned son of a rat-catcher who lived in the sewers of the city before he was brought to the castle to serve as the whipping boy for Prince Brat, as he was not so lovingly referred to by his subjects. Each time the Prince did something wrong, Jemmy was whipped. Because the Prince was bored, he decided to run away and Jemmy was to go with him to serve as his man-servant. The two soon run into trouble and many fabulous characters as they navigate around the city hiding from the king's men who were searching for the Prince. As the two boys overcome many obstacles, they slowly become friends. They eventually make their way back to the palace where all is forgiven and the two boys remain friends and companions - with no more whippings!

In the author's note at the end of the book, Fleishman says, "History is alive with lunacies and injustices." I suppose that is why I spent six years of my life studying history with all of its insanity!

Flusi

PS. If you are a librarian (or even if you aren't I suppose), check out the YouTube post at my work related blog, LibrarysCat. It is a wonderful affirmation of what we, as librarians, should be doing to move the field into the 21st century! Also, this book post will be posted at my book blog Now that my required work blogging is done, I can concentrate more on reading!

Monday, July 30, 2007

A Visit to William Blake's Inn

is subtitled Poems for Innocent and Experienced Travelers, was written by Nancy Willard, illustrated by Alice and Martin Provensen, and won the Newbery Medal in 1982.

is subtitled Poems for Innocent and Experienced Travelers, was written by Nancy Willard, illustrated by Alice and Martin Provensen, and won the Newbery Medal in 1982.I felt like I was on a roll with children's poetry - I absolutely loved Out of the Dust, and I liked Joyful Noise very much. Last week I picked up my son's copy of A Pizza the Size of the Sun (by Jack Prelutsky) and read it without even meaning to do so before re-shelving it. And I have always liked "Tyger, Tyger, burning bright, In the forests of the night" (the only William Blake poem I can remember), so I thought that A Visit to William Blake's Inn was a good bet for my next read.

I was a little disappointed. It's a short book, shelved with the younger kids' picture books in our library (it won Caldecott honors in addition to the Newbery award), and I just didn't find the the sixteen poems and the accompanying illustrations about an imaginary inn run by William Blake terribly compelling. I like reading about (and watching video re-creations of) Regency period England, too. I just moved Pride & Prejudice (both recent versions) up on my Netflix queue. Again. Not just so I can see Colin Firth swimming, either.

The poems and the illustrations do have a certain charm reminiscent of old nursery rhymes, and they suit each other very well. But I would be very surprised if this were a favorite of many kids. I can see that some adults would enjoy it (especially if you have a fondness for early 19th century England) - but this is supposed to be an award for children's literature, not children's literature written for adults, and that's how this book struck me.

The Wise Cow Enjoys a Cloud

"Where did you sleep last night, Wise Cow?

Where did you lay your head?"

"I caught my horns on a rolling cloud

and made myself a bed,

and in the morning ate it raw

on freshly buttered bread." (p. 26)

Saturday, July 28, 2007

Feeling Pensieve about The Giver

In her blog, Bookworm recently posed a question about how one might differentiate between a literary homage and a literary rip-off. As I read The Giver (published in 1993), I was fascinated to see myself staring into Dumbledore’s pensieve (first revealed in Harry Potter and the Goblet of Fire, published in 2000) as the bearded, elderly mentor chose memories (magically presented from an omniscient point of view) to share with his youthful pupil. Receipt of the memories is a bittersweet experience for the student. In Harry Potter, the pensieve is a useful tool for a privileged few to access. In The Giver, memories are forbidden for most people. In each case, the pupil had been pre-ordained to bear a great burden on behalf of the community, and needed to be fortified with knowledge from the past in order to free loved ones from unpleasantness that would otherwise befall them.

In her June post about The Giver, Alicia asked: Is it possible to create a compelling story (about regimented eu/dys-topias) in which the protagonist is persuaded by the merits of and chooses to remain and support the society despite knowledge of its shortfalls? The wizarding world doesn’t nearly reach the level of regimentation of the society described by Lois Lowry (others have pointed out The Giver’s similarities to the planet in A Wrinkle in Time, and I also recall a Star Trek: Next Generation episode, in which Wesley Crusher had a close call after falling into a flowerbed). Taking gifted children away from their families to be schooled at Hogwarts, a sorting hat and a room full of prophecies are the main things I can think of where Rowling approaches regimentation.

Homage? I loved both books, but it is interesting to see how one author (perhaps) draws inspiration from another and uses it in a new way. J.K. Rowling and Lois Lowry both explore memory, using similar devices, and reach somewhat similar conclusions about the value of love, loyalty and innocence. I’ve got no problem with reinforcing those lessons. I’ll vote for homage.

In her June post about The Giver, Alicia asked: Is it possible to create a compelling story (about regimented eu/dys-topias) in which the protagonist is persuaded by the merits of and chooses to remain and support the society despite knowledge of its shortfalls? The wizarding world doesn’t nearly reach the level of regimentation of the society described by Lois Lowry (others have pointed out The Giver’s similarities to the planet in A Wrinkle in Time, and I also recall a Star Trek: Next Generation episode, in which Wesley Crusher had a close call after falling into a flowerbed). Taking gifted children away from their families to be schooled at Hogwarts, a sorting hat and a room full of prophecies are the main things I can think of where Rowling approaches regimentation.

Homage? I loved both books, but it is interesting to see how one author (perhaps) draws inspiration from another and uses it in a new way. J.K. Rowling and Lois Lowry both explore memory, using similar devices, and reach somewhat similar conclusions about the value of love, loyalty and innocence. I’ve got no problem with reinforcing those lessons. I’ll vote for homage.

Tuesday, July 24, 2007

More Love for the Hero and the Crown

Like Melissa, I read The Hero and The Crown a long time ago. I was an adult, but I've always liked fantasy, and when this was publicized as award-winning YA fantasy, I eagerly picked it up and wasn't disappointed. I went on to read everything that Robin McKinley published (which has not been nearly enough over the years!), most recently Sunshine - a post-apocalyptic vampire story - and I've loved them all. So I'm hardly an objective reviewer either.

Like Melissa, I read The Hero and The Crown a long time ago. I was an adult, but I've always liked fantasy, and when this was publicized as award-winning YA fantasy, I eagerly picked it up and wasn't disappointed. I went on to read everything that Robin McKinley published (which has not been nearly enough over the years!), most recently Sunshine - a post-apocalyptic vampire story - and I've loved them all. So I'm hardly an objective reviewer either.I never re-read The Hero and the Crown after I discovered it in the late 80's, though, so when I picked it up last week I really couldn't remember why I loved it so much, nor many of the details of the story.

It didn't take me long to realize that (again, like Melissa) it was the writing and the characters - especially Aerin, the main character - that really got to me. Like J.R.R. Tolkien (sorry, but that's what got me hooked so hard on fantasy as a child), McKinley combines the mythical and the down-to-earth perfectly. And furthermore, she writes about a young girl, the rescue of a beautiful and intelligent horse, dragons, and secret powers - I would have read this and re-read it countless times if it had been out when I was an adolescent. Now, I noticed how cleverly that McKinley portrayed Aerin as a likable, irreverant, smart outsider - much like Rae in Sunshine, come to think of it.

There are a few things that bothered me a bit this time around. McKinley does an incredible job of world-building, but the Damarian names for things jarred sometimes. I didn't mind sol and sola (princes and princesses) so much, but hafor (for "folk of the household") and yerig and folstza and a few other terms interrupted the narrative unnecessarily.

There are two love stories in the book - I liked them both, and the more than "happily ever after" ending was a refreshing change. Funny how I completely forgot about Luthe (and pretty much Tor, too) since the first time I read The Hero and the Crown. Mostly I remembered Aerin, her horse, and the dragon. But although there's nothing particularly explicit about Aerin's relationship with Luthe, I think that it makes the book more appropriate for older Newbery readers. Plus, the writing (though exquisite), can be rather intense. Take this excerpt about despair:

A blast of grief, of the deaths of children, of crippling diseases that took beauty at once but withheld death; of unconsummated love, of love lost or twisted and grown to hate; of noble deeds that proved useless, that broke the hearts of their doers; of betrayal without reason, of guilt without penance, of all the human miseries that have ever occurred; all this struck them, like the breath of a slaughterhouse, or the blow of a murderer. (p. 208).Have you ever read a more poetic description of despair and depression? Luckily, it is overcome, and the story ends happily with puppies and kittens and love. For a while, anyway, and isn't that the case in real life, too?

Tuesday, July 17, 2007

Hero and the Crown

I told myself when I signed on to this project, that I wasn't going to read any of the Newbery's that I've already read. Then Alicia came up with her July challenge, and I noticed that no one else has read this one, by Robin McKinley, yet. And I figured it was about time to re-visit this old friend.

There is no way I can give this book an objective review; it is one of the few that solidified my love of YA books as well as earning McKinley a special place in my heart and on my shelves. I love it. I have loved it since I first read it, which wasn't as long ago as it should have been (I was only 12 in 1984 when this book came out; this was one book I should have read, and would have loved, when I was that age. But I missed it completely.)

It's a companion book to The Blue Sword (if you haven't read that one, you should. It was written first, but you can read these two in any order), though it takes place centuries before. Aerin is the daughter of Damar's king, Arlbeth, though she's not comfortable in that place. For one, her mother was a foreigner, a Northerner, and not especially trusted. And she's often despised and ridiculed for existing. She does have one friend, Tor, who sticks up for her, teaches her swordplay and horsemanship, and eventually falls in love with her. Aerin tries to find her place in a world that she doesn't feel she belongs in. After a near-fatal accident, she discovers a recipe of sorts for kenet, which eventually leads her to being able to fight the little dragons that annoy and disturb the countryside. That leads, on one fateful day, to her facing the Black Dragon, Maur, and from there, discovering and embracing her destiny.

It's a marvelous tale. Aerin is perfect: headstrong, lovable, understandable. What girl hasn't felt that she fit in? What girl doesn't long to make her parents proud, but is ashamed of her insecurity? What girl doesn't want to know how she can make a difference? Aerin is one of those characters that you embrace and cheer and understand and love. And whose courage and bravery seem not super-heroic, but real and attainable.

This conversation takes place soon after Aerin kills her first dragon, and is, afterward, sworn to serve the king:

There is no way I can give this book an objective review; it is one of the few that solidified my love of YA books as well as earning McKinley a special place in my heart and on my shelves. I love it. I have loved it since I first read it, which wasn't as long ago as it should have been (I was only 12 in 1984 when this book came out; this was one book I should have read, and would have loved, when I was that age. But I missed it completely.)

It's a companion book to The Blue Sword (if you haven't read that one, you should. It was written first, but you can read these two in any order), though it takes place centuries before. Aerin is the daughter of Damar's king, Arlbeth, though she's not comfortable in that place. For one, her mother was a foreigner, a Northerner, and not especially trusted. And she's often despised and ridiculed for existing. She does have one friend, Tor, who sticks up for her, teaches her swordplay and horsemanship, and eventually falls in love with her. Aerin tries to find her place in a world that she doesn't feel she belongs in. After a near-fatal accident, she discovers a recipe of sorts for kenet, which eventually leads her to being able to fight the little dragons that annoy and disturb the countryside. That leads, on one fateful day, to her facing the Black Dragon, Maur, and from there, discovering and embracing her destiny.

It's a marvelous tale. Aerin is perfect: headstrong, lovable, understandable. What girl hasn't felt that she fit in? What girl doesn't long to make her parents proud, but is ashamed of her insecurity? What girl doesn't want to know how she can make a difference? Aerin is one of those characters that you embrace and cheer and understand and love. And whose courage and bravery seem not super-heroic, but real and attainable.

This conversation takes place soon after Aerin kills her first dragon, and is, afterward, sworn to serve the king:

Aerin and her father looked at each other. For the first time she had official position in his court; she had not merely been permitted her place, as she had grudgingly been permitted her undeniable place at his side as his daughter, but she had won it. She carried the king's sword, and thus was, however irregularly, a member of his armies and his loyal sworn servant as well as his daughter. She had a place of her own -- both taken and granted. Aerin clutched the spears to her breast, painfully banging her knee with the sword scabbard in the process. She nodded.And McKinley's writing is nearly flawless (there's a place at the end where you have to read through a couple of times to get what happened). This is when Aerin faces Maur:

"Good. If you had remained hidden, I would have sent Gebeth again -- and think of the honor you would have lost. "

Aerin, who seemed to have lost her voice instead, nodded again.

"Another lesson for you, my dear. Royalty isn't allowed to hide -- at least not once it has declared itself."

A little of her power of speech came back to her, and she croaked, "I have hidden all my life."

Something like a smile glimmered in Arlbeth's eyes. "Do I not know this? I have thought more and more often of what I must do if you did not stand forth of your own accord. But you have -- if not quite in the manner I might have wished -- and I shall take every advantage of it."

Maur raised its head with a snap, and the spear bounced harmlessly off the horny ridge beneath its eye; and Talat lurched out of the way of the striking tail. The dragon's head snaked around as Talat evaded the tail, and Talat dodged again, and fire sang past Aerin's ear, fire like nothing either Talat or Aerin had seen before, any more than this dragon was like any other dragon they had seen. The fire was nearly white, like lightning, and it smelled hard and metallic; it smelled like the desert at noon, it smelled like a forest fire; and the blast of air that sheathed it was hotter than any Damarian forge.There really isn't much more to say about it. It's one of my favorites, and may always be. It's also become one of my oldest daughter's favorites, something which I'm very happy about. And not just because it's an excellent book. But because it's an excellent book about an admirable girl.

Saturday, July 14, 2007

Joyful Noise

I liked the 1989 winner, Joyful Noise: Poems for Two Voices, by Paul Fleischman quite a bit - but I think I would have been more impressed by it if I hadn't just read Karen Hesse's gut-wrenchingly powerful and beautiful poetry in Out of the Dust.

I liked the 1989 winner, Joyful Noise: Poems for Two Voices, by Paul Fleischman quite a bit - but I think I would have been more impressed by it if I hadn't just read Karen Hesse's gut-wrenchingly powerful and beautiful poetry in Out of the Dust.Joyful Noise is a collection of fourteen short poems about insects, written in two columns and meant to be read aloud by two people (ideally, you & your child). The "joyful noise" refers to the cicada poem, but could just as well mean your reading. Some lines are meant to be read together, but when my ten-year-old son and I spoke in unison, it didn't sound as good as I thought it would. I liked the alternating lines better - but I did really enjoy the reading aloud part. He tolerated it, because he loves insects.

The "read aloud" aspect, especially with two people, was pretty innovative. And I adored the black and white illustrations by Eric Beddows, which added a whole different dimension to the book, with quirky little moths, whiligig beetles, mayflies, etc.

My favorite poem was "Book Lice" (this is just a snippet of it):

I missed Conan DoyleBut I did wonder how many kids got all the author references.

he pined for his Keats

We're book lice

fine mates

despite different tastes. (p. 17)

My son's favorite poem was the tragic "Moth's Serenade" (to the porch light!). But when I told him to write the book down in his list for our library's summer reading program (prizes for every five books, and a big one at the end after 15 books) he refused, arguing that "it's too short to be a real book for my age". What a weird kid.

I did think that Joyful Noise was kind of light-weight compared to most of the other Newbery winners I've read so far - both in length (44 pages) and in subject. I'll bet the judges were just so blown away by the format, that they chose it anyway. I'm rather glad that they did - because I probably would never have read it otherwise.

PS What is it about insects that make them such a popular topic for kid's poetry? This reminded me of another (very different, but equally enjoyable) more recent book: Song of the Water Boatman & Other Poems, by Joyce Sidman, illustrated by Beckie Prange.

1960 Winner, Onion John

I zipped through Joseph Krumgold's Onion John while previewing materials for potential lesson plans relating to the theme of fatherhood two years ago. The reconciliation of a father and son is the focus of the novel. Here is what I wrote about it in the annotated list of resources for the paper:

"Boy befriends a homeless man in small town New Jersey. Boy is the only person who can understand the man through his speech impediment. Father objects but later mellows and stops pressuring boy to become an engineer. Boy expresses admiration for father. Homeless man goes away. Seems dated and ending is too pat."

To be fair, my reading was cursory and I might have gotten more out of the book if I had decided to focus on it for use in my lesson plans. I remember thinking that a present-day Newbery author or reviewer would probably be more concerned about showing the boy's growing understanding of the issues of homelessness.

I wished Krumgold had done a better job of tying up the loose end regarding the eventual fate of Onion John. Apparently, the homeless man simply goes on to live in a different place and the boy goes on with his life. I suppose I should recognize that as the reality of poverty and homelessness, and not expect that a contemporary version would provide a more satisfying resolution of that part of the story.

"Boy befriends a homeless man in small town New Jersey. Boy is the only person who can understand the man through his speech impediment. Father objects but later mellows and stops pressuring boy to become an engineer. Boy expresses admiration for father. Homeless man goes away. Seems dated and ending is too pat."

To be fair, my reading was cursory and I might have gotten more out of the book if I had decided to focus on it for use in my lesson plans. I remember thinking that a present-day Newbery author or reviewer would probably be more concerned about showing the boy's growing understanding of the issues of homelessness.

I wished Krumgold had done a better job of tying up the loose end regarding the eventual fate of Onion John. Apparently, the homeless man simply goes on to live in a different place and the boy goes on with his life. I suppose I should recognize that as the reality of poverty and homelessness, and not expect that a contemporary version would provide a more satisfying resolution of that part of the story.

Kids' Views of The View from Saturday

First-year teacher makes a bad choice.

My 7th grade students actively hated Konigsburg’s, The View From Saturday (TVFS). From the cover, showing teacups and a Victorian architectural feature (“looks boring”), to the substance (the first major chapter focuses at length on the wedding of grandparents at a Florida retirement community), to the pedantic qualities (laboriously-constructed symbolism involving a heart-shaped-jigsaw, for instance, and vocabulary and history and natural science and trivia and morality lessons incorporated into the plot), to confusing use of repetition (some incidents are related from the point of view of more than one character).

In the manner of the recent Newbery controversy around the word “scrotum,” some of my students could not get over what seemed like a gratuitous reference to bra straps and (to them) titillating use of the word “puberty” on the second page.

After my class finished the book, I found comments inside the back cover where Konigsburg described using four separate short stories from her files to construct TVFS around a common theme. Although she wrote that readers have told her that, “fitting all the stories together is part of the adventure,” it was the disjointed origins of the stories that came across to me as I read the book.

One more thing. The main characters of TVFS form a team to compete in the middle school Academic Bowl. The principal of a competing school tells their teacher, “I told our coach that she could expect to be hung if she lets your sixth grade grunges beat us out.” The teacher replies, “I recommend that you start buying rope.” Apparently because of this conversation, the noose becomes the symbol for the team – their fans wear small nooses on their shirts, they hang a noose from a car antenna, and grandparents have custom-made t-shirts with nooses sold as a fundraiser. I did a double-take when the noose began to reappear as a symbol, and had to go back and comb through the book to figure out its origin and meaning. In what universe would thoughtful adults encourage the use of a noose as an inspiration for a school team of any kind?

The theme of building diverse communities through kindness to others is lovely, of course, and the one bright spot for the kids involved learning about sea turtles. For the most part, though, the book read like an out-of-touch adult’s idea of what a contemporary adolescent should care about, not what a young reader would actually want to read.

Newbery Committee makes a bad choice?

My 7th grade students actively hated Konigsburg’s, The View From Saturday (TVFS). From the cover, showing teacups and a Victorian architectural feature (“looks boring”), to the substance (the first major chapter focuses at length on the wedding of grandparents at a Florida retirement community), to the pedantic qualities (laboriously-constructed symbolism involving a heart-shaped-jigsaw, for instance, and vocabulary and history and natural science and trivia and morality lessons incorporated into the plot), to confusing use of repetition (some incidents are related from the point of view of more than one character).

In the manner of the recent Newbery controversy around the word “scrotum,” some of my students could not get over what seemed like a gratuitous reference to bra straps and (to them) titillating use of the word “puberty” on the second page.

After my class finished the book, I found comments inside the back cover where Konigsburg described using four separate short stories from her files to construct TVFS around a common theme. Although she wrote that readers have told her that, “fitting all the stories together is part of the adventure,” it was the disjointed origins of the stories that came across to me as I read the book.

One more thing. The main characters of TVFS form a team to compete in the middle school Academic Bowl. The principal of a competing school tells their teacher, “I told our coach that she could expect to be hung if she lets your sixth grade grunges beat us out.” The teacher replies, “I recommend that you start buying rope.” Apparently because of this conversation, the noose becomes the symbol for the team – their fans wear small nooses on their shirts, they hang a noose from a car antenna, and grandparents have custom-made t-shirts with nooses sold as a fundraiser. I did a double-take when the noose began to reappear as a symbol, and had to go back and comb through the book to figure out its origin and meaning. In what universe would thoughtful adults encourage the use of a noose as an inspiration for a school team of any kind?

The theme of building diverse communities through kindness to others is lovely, of course, and the one bright spot for the kids involved learning about sea turtles. For the most part, though, the book read like an out-of-touch adult’s idea of what a contemporary adolescent should care about, not what a young reader would actually want to read.

Newbery Committee makes a bad choice?

Thursday, July 5, 2007

Independence Day and the Westing Game

Yesterday when I was browsing through the Newbery winners on hand, trying to decide which one to read next, I knew that I had to read The Westing Game when I saw this sentence on the first page:

Yesterday when I was browsing through the Newbery winners on hand, trying to decide which one to read next, I knew that I had to read The Westing Game when I saw this sentence on the first page:Then one day (it happened to be the Fourth of July), a most uncommon-looking delivery boy rode around town slipping letters under the doors of the chosen tenants-to-be.How cool is that, I read about it on the same day (well, a couple decades later) that the story started.

The Westing Game was a great read for a summer day (and evening): relaxing, and interesting enough to keep me turning pages, but not so compelling that I couldn't put it down when it was time to go swimming or catch fireflies. And after reading a couple of very intense, emotionally wrenching stories in the last week, I found this mystery by Ellen Raskin pretty refreshing. It's the YA/older elementary kid's equivalent of Janet Evanovich - so I'm a little surprised that it won the Newbery award, actually. Maybe there were a lot of mystery lovers on the selection committee in 1979.

It is probably more accurate to compare The Westing Game to vintage Agatha Christie than to Janet Evanovich - there's no sex, and no cars blow up in TWG. It's a classic "closed house" murder mystery, complete with an eccentric, manipulative millionaire with a ridiculously strange will, and a huge cast of characters (it may be useful to have a printout from a site like this one at The Westing Heirs on hand to keep every one straight). There are numerous plot twists - some really obvious (especially in retrospect, if you read a lot of mysteries), and others that are totally unanticipated.

In a lot of ways, this reminded me of a cheesy 80's movie - something about the tone of the story, with its unabashedly greedy characters - and when I looked around the net, sure enough The Westing Game movie (also called Get a Clue!, but not to be confused with the 2002 Lindsey Lohan movie without an exclamation point) was made in 1997. Ray Walston played Sandy McSouthers and Diane Ladd played Berthe Erica Crow, but I've never heard of the rest of the cast. I guess it was a kind of a forgettable movie.

The Westing Game wasn't profound, but it was fun, especially if you like codes, clues, spooky mansions, and chess, and I'll bet I would have absolutely loved it if I'd read it when I was twelve.

Tuesday, July 3, 2007

Dust

I was intrigued by Flusi's post on Out of the Dust, the 1998 winner by Karen Hesse. Every time I read poetry, I wonder why I don't read more of it, because I enjoy it so much. I was probably the only person in my high school literature class that liked the "introduction to poetry" text so much that I went and bought my own copies of Leaves of Grass and the Spoon River Anthology. But in the years since then, although I've read a lot, poetry hasn't made up much of what I've read.

Hesse's book didn't disappoint me - the poems are beautiful, and haunting, and describe a time and a place (Oklahoma's panhandle in the early 1930's) so well that I really felt transported. The things that Hesse writes about - dust, over and over again, throughout the book, gritty and heavy and so pervasive - but also pregnancy, horrible accidents, rain, apples, music, and the longing to run away - they really tell a very powerful story. In that respect Out of the Dust reminded me of those intertwined stories in the Spoon River Anthology. And Billie Jo? She's more than a little like an older Caddie Woodlawn, with her red hair, different conflicts with her parents, and her independent nature.

I do think that Out of the Dust is better for kids on the older edge of the Newbery award readers - like a few other books I've read recently (like The Birchbark House, and A Thousand Splendid Suns), the sudden death and grief in Out of the Dust are not "easy" topics, for either adults or kids.

But the beauty, redemption, and hope (in all of the books above, actually) make them so worth it.

Hesse's book didn't disappoint me - the poems are beautiful, and haunting, and describe a time and a place (Oklahoma's panhandle in the early 1930's) so well that I really felt transported. The things that Hesse writes about - dust, over and over again, throughout the book, gritty and heavy and so pervasive - but also pregnancy, horrible accidents, rain, apples, music, and the longing to run away - they really tell a very powerful story. In that respect Out of the Dust reminded me of those intertwined stories in the Spoon River Anthology. And Billie Jo? She's more than a little like an older Caddie Woodlawn, with her red hair, different conflicts with her parents, and her independent nature.

I do think that Out of the Dust is better for kids on the older edge of the Newbery award readers - like a few other books I've read recently (like The Birchbark House, and A Thousand Splendid Suns), the sudden death and grief in Out of the Dust are not "easy" topics, for either adults or kids.

But the beauty, redemption, and hope (in all of the books above, actually) make them so worth it.

Almost Rain

It almost rained Saturday.

The clouds hung low over the farm.

The air felt thick.

It smelled like rain.

In town,

the sidewalks

got damp.

That was all.

November 1934 (p. 88)

Challenge response: Roller Skates

In response to the July challenge, I'll tell you about Roller Skates by Ruth Sawyer. First, I have to say that I have an older copy of the book--a hardback edition from 1949 with incredible illustrations by Valenti Angelo. Second, I've read this book twice now and loved it both times, but especially this time around because of these amazing line drawings.

Roller Skates is the story of Lucinda, a little girl who gets to be an "orphan" in New York City while her family travels to Europe. She barely escapes living with her horrible Aunt Emily who has very definite ideas about how girls should behave and lives instead with Miss Peters and Miss Nettie, two single women who treat Lucinda as very much older than her ten years. Lucinda comes and goes as she pleases--mostly on her roller skates.

The book tells of Lucinda's adventures of meeting wonderful people outside of her normal life--people like Patrolman M'Gonegal, Mr. Gilligan the hansom cab driver and his wife, Trinket the little girl Lucinda "borrows" from upstairs, the Princess Zayda to whom Lucinda teaches English, Tony the boy who manages the fruit stand and his Italian family who lives in a basement--people Lucinda would not normally come into contact with were her family home. Roller Skates is a story of freedom and escaping the rules and regulations of growing up--a story of belonging entirely to yourself and skating where you will.

I do love books that tell of a different time--a time when children were safe to run and roam and explore their worlds. The idea of a girl exploring New York City on skates seems unreal in some ways to me--and, in a way, it was unreal in the time it was written too. And that's the timeless appeal of the story--the freedom of this season in Lucinda's life to be just herself. She realizes its uniqueness too, for at the end of the story she realizes "she'd never belong to herself again," never have another summer of being free and being ten years old.

I loved roller skating as a kid--and think I may need to get out my skates!

Roller Skates is the story of Lucinda, a little girl who gets to be an "orphan" in New York City while her family travels to Europe. She barely escapes living with her horrible Aunt Emily who has very definite ideas about how girls should behave and lives instead with Miss Peters and Miss Nettie, two single women who treat Lucinda as very much older than her ten years. Lucinda comes and goes as she pleases--mostly on her roller skates.

The book tells of Lucinda's adventures of meeting wonderful people outside of her normal life--people like Patrolman M'Gonegal, Mr. Gilligan the hansom cab driver and his wife, Trinket the little girl Lucinda "borrows" from upstairs, the Princess Zayda to whom Lucinda teaches English, Tony the boy who manages the fruit stand and his Italian family who lives in a basement--people Lucinda would not normally come into contact with were her family home. Roller Skates is a story of freedom and escaping the rules and regulations of growing up--a story of belonging entirely to yourself and skating where you will.

I do love books that tell of a different time--a time when children were safe to run and roam and explore their worlds. The idea of a girl exploring New York City on skates seems unreal in some ways to me--and, in a way, it was unreal in the time it was written too. And that's the timeless appeal of the story--the freedom of this season in Lucinda's life to be just herself. She realizes its uniqueness too, for at the end of the story she realizes "she'd never belong to herself again," never have another summer of being free and being ten years old.

I loved roller skating as a kid--and think I may need to get out my skates!

Monday, July 2, 2007

Another Holes Post

My son actually picked up Holes first at the library. Since I was attempting to read in order, starting from the oldest, I hadn't gotten to it yet. But since he had it, I figured I'd read it. I'd previously seen the movie, and I must say that I much prefer reading and then watching a movie to the other way around. My sister ended up choosing this book for a Book Club she's with, and in comparing my feelings about the book in contrast with theirs, I could see how much of the anticipation and surprise of the twists I missed already knowing the outcome. That said, I appreciate how closely the movie parallels the book, because that is so rare in movie adaptations.

Holes has a surprising amount of depth (unintended pun, sorry) to the story. You don't expect that when you first pick it up. It seems like just another adventure story about an unfortunate boy sent to a work camp for a crime he didn't commit. But once well into the novel, you realize that there are deep themes of racism and interpersonal relationships expertly woven into the tale.

Previous posts have discussed how much subtle and overt racism earlier Newbery titles contain, as a reflection of their era. While these books can open a discussion about racism and its consequences, if such happens, it needs to be done in a deliberate manner. Holes on the other hand, vividly illustrates the ugliness of racism in a way that children can grasp without having to be led to the recognition. This might make Holes a good read before exposing your children to some of the earlier novels, so that your child can initiate a conversation about these themes making them more open to recognizing how behaviors and language in older books are not acceptable now, and were unjust then.

Holes has a surprising amount of depth (unintended pun, sorry) to the story. You don't expect that when you first pick it up. It seems like just another adventure story about an unfortunate boy sent to a work camp for a crime he didn't commit. But once well into the novel, you realize that there are deep themes of racism and interpersonal relationships expertly woven into the tale.

Previous posts have discussed how much subtle and overt racism earlier Newbery titles contain, as a reflection of their era. While these books can open a discussion about racism and its consequences, if such happens, it needs to be done in a deliberate manner. Holes on the other hand, vividly illustrates the ugliness of racism in a way that children can grasp without having to be led to the recognition. This might make Holes a good read before exposing your children to some of the earlier novels, so that your child can initiate a conversation about these themes making them more open to recognizing how behaviors and language in older books are not acceptable now, and were unjust then.

July Challenge

So the Newbery Project has been in existence for six months now. How are people feeling about it?

If you look in the sidebar, you'll see that certain books -- by luck or by design -- are getting more traffic than others. Caddie Woodlawn is especially popular, particularly among the older books. Meanwhile 4 books from the 1990s have had no posts. Curious.

Let me throw out a July Challenge: each of us read and post on one of the Newbery books that has thus far gone untouched.

What do you think?

I happen to have started Dobry (1935's winner) a few weeks ago and will read it regardless.

Just trying to liven things up here.

If you look in the sidebar, you'll see that certain books -- by luck or by design -- are getting more traffic than others. Caddie Woodlawn is especially popular, particularly among the older books. Meanwhile 4 books from the 1990s have had no posts. Curious.

Let me throw out a July Challenge: each of us read and post on one of the Newbery books that has thus far gone untouched.

What do you think?

I happen to have started Dobry (1935's winner) a few weeks ago and will read it regardless.

Just trying to liven things up here.

Sunday, July 1, 2007

Caddie Woodlawn--again!

I quit reading for a while, but now with long summer afternoons at the pool working on a tan and watching the girls jump off the diving board, I'm back in the swing of things--because nothing goes with lounging by the pool like a good book!

Yesterday afternoon I read Caddie Woodlawn. I'm a sucker for pioneer girl stories, so it seemed a natural choice when I was at the bookstore. I was surprised by the endorsement on the back: "You take Little House on the Prarie; I'll take Caddie Woodlawn." Better than Little House? That's a pretty big claim.

Caddie Woodlawn didn't remind me so much of the Little House books--they have much more adventure, I think, and more of a sweeping pioneer feel. Caddie takes place in one location and I didn't really get the sense that the Woodlawns were a pioneer family, despite the worry about Indians and waiting for news from the east. All in all, the Woodlawns seemed pretty connected with the rest of the world compared to the Ingalls family.

This book reminded me more of the Grandmother's Attic books--especially after reading the author's note at the front of my copy.

All that to say, I did enjoy Caddie Woodlawn immensely and look forward to reading it with my girls. I can see them using this book for a school project at some point--and my copy (2006, Aladdin Paperbacks) has a great reader's guide at the end that has some good discussion questions and also some research and activity ideas. Though the book does leave out some historical details and raises questions like the ones in the previous post (which seemed somewhat real to me--as an 11-year-old girl, Caddie is more concerned with the small world she lives in rather than the world at large), it is a good way to interest kids in doing some research of their own.

Yesterday afternoon I read Caddie Woodlawn. I'm a sucker for pioneer girl stories, so it seemed a natural choice when I was at the bookstore. I was surprised by the endorsement on the back: "You take Little House on the Prarie; I'll take Caddie Woodlawn." Better than Little House? That's a pretty big claim.

Caddie Woodlawn didn't remind me so much of the Little House books--they have much more adventure, I think, and more of a sweeping pioneer feel. Caddie takes place in one location and I didn't really get the sense that the Woodlawns were a pioneer family, despite the worry about Indians and waiting for news from the east. All in all, the Woodlawns seemed pretty connected with the rest of the world compared to the Ingalls family.

This book reminded me more of the Grandmother's Attic books--especially after reading the author's note at the front of my copy.

All that to say, I did enjoy Caddie Woodlawn immensely and look forward to reading it with my girls. I can see them using this book for a school project at some point--and my copy (2006, Aladdin Paperbacks) has a great reader's guide at the end that has some good discussion questions and also some research and activity ideas. Though the book does leave out some historical details and raises questions like the ones in the previous post (which seemed somewhat real to me--as an 11-year-old girl, Caddie is more concerned with the small world she lives in rather than the world at large), it is a good way to interest kids in doing some research of their own.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)