Wednesday, December 1, 2010

Ginger Pye

Well, I was wrong on a couple counts. First all, although Ginger Pye was published in 1951, it's set in a much earlier era. I sat and tried to figure out exactly when the story took place by thinking about the trains, the "jalopies", and the general technology used in the story (milking cows by hand, gas lights, pier-glass mirrors, a "horsehair parlor"), but not a whole lot of date-specific things are actually mentioned in Estes' fictional town of Cranbury (which I later read was based on West Haven, CT), which is located somewhere between Boston and New York.

I turned to the Internet next, where people stated with great certainty (and in all but one case, mistakenly) that the story was set in 1919, 1924, the 1950's, and even the 1960's and 70's. The latter dates were a particular stretch, given the book's publication date and the fact that it is NOT science fiction. Anyway, one post mentioned the date on a newspaper in one of Estes' illustrations (on pg. 161), and I checked, and it is indeed 1919. This is a bit earlier than I would have guessed, but since the story is such a timeless one - based entirely on the activities of a couple kids, their family, their dog, and a couple of neighbors - the date doesn't actually matter much.

The second thing I was mistaken about was that the story was going to be charming. I didn't find Ginger's story (or more accurately, Jerry and Rachel's story) charming so much as mostly insipid and meandering.There were a few nice parts - I particularly liked Rachel's "reasonable unreasonableness" - but mostly, I was bored. I did like Ginger's point of view, and the ending was rather satisfying - but these were little sparks of interest in a sea of wholesome family bland. Maybe reading it right after Roll of Thunder, Hear My Cry was a mistake, because I couldn't help comparing the sibling interactions, the historical setting, and lots more in the two books, with Ginger Pye coming up distinctly lacking.

I didn't care about the Unsavory Character (a man in a yellow hat, not to be confused with the one in Curious George), I hated Estes' illustrations (shown here on the original cover), and the most fun I had was comparing the historical differences of kid behavior and parenting then and now. Talk about your free-range kids (and dogs - leashes were not just optional but totally disparaged).

Jerry and Rachel (ages 10 and 9, respectively) go swimming at the reservoir by themselves, sometimes taking their 3 year old Uncle Bennie with them. One of their favorite places to play is on a "skeleton house" - the framework of a house under construction. If this were gritty realism instead of an idyllic small town story, someone would have drowned, or fallen into the basement hole from the top floor scaffolding, or gotten tetanus, or something like that. Even German measles (rubella) wasn't a big deal in the book. There just wasn't enough drama for me, even when things did happen. And the fact that Jerry and Rachel's mother met their father when she was 17 and he was 35 didn't seem quite so romantic to me as it was told in the book, though the fact that he was a famous "bird man" (aka an ornithologist) was a little interesting - but not enough to make me truly care.

I haven't read anything else by Eleanor Estes, so I'd be interested in hearing how this compares to her other books, which people talk about with some affection. I can see how some people might enjoy the rambling narratives by Jerry, Rachel, and Ginger....but I really didn't get much out of it.

Friday, November 26, 2010

A Foreboding Roll of Thunder

After reading the first five chapters, I was filled with foreboding, waiting for a major character to be horribly killed or wounded. It didn't help that I had read Sounder not too long before I started Roll of Thunder.

I had the same feeling when I started reading The Kite Runner a few years ago, which I also put off reading for a couple years despite the fact that it seemed like half the people I know had already read it and recommended it. What can I say? One reason I read is for relaxation and escape, and I don't generally like Oprah-esque literary fiction. I did end up being very happy that I read The Kite Runner, mind you.

Then I got a part-time writing job, and happily abandoned Roll of Thunder (and indeed, all the remaining winners I hadn't yet read), and filled my drastically reduced reading time with books that didn't engender feelings of impending doom.

I finished my job last month, and finally returned to Roll of Thunder again. I was still worried about the characters - and reading They Called Themselves the KKK by Susan Campbell Bartoletti (one of the books in the running for this year's Newbery prize) just before resuming Roll of Thunder didn't exactly make me feel any better about Cassie, Stacey, Christopher-John, Little Man, and their extended family's prospects in Mississippi in the 1930's. It was pretty depressing. So I did something that I know drives some people crazy - I skipped ahead and read the last couple of pages. I wanted to be prepared for the worst that Mildred D. Taylor could throw at me.

Well, I could tell from the last few pages that Taylor's worst wasn't unbearable, and so I was able to finish the book with less foreboding, not wincing quite so much at the (sometimes heavy) foreshadowing, or every time Cassie lost her temper. I have to say that Taylor did an excellent job of describing the Logan siblings, and she used history - as in Mr. Morrison's Reconstruction-era story that he told on Christmas, which could have come straight out of They Called Themselves the KKK - very skillfully. The history doesn't ever overpower the Logans' story, but it serves as powerful backdrop, enriching the plot and putting the the characters' actions into a carefully constructed and entirely believable context.

It's a timeless book, too - Roll of Thunder, Hear My Cry was written in 1976, but you really couldn't tell, unlike some of the other Newbery winners that feel a bit dated now (like Summer of the Swans, for instance, or It's Like This, Cat). I wonder if this accounts for some of the appeal that historical fiction seems to hold the Newbery Committee. At any rate, Roll of Thunder reads like a classic. And yes, parts of it were disturbing, but it was not a horribly depressing book. I actually want to read some of Mildred Taylor's other books about the Logan family now!

Thursday, October 28, 2010

Good Masters! Sweet Ladies! by Laura Amy Schlitz

Tuesday, October 12, 2010

The Midwife's Apprentice

Monday, October 11, 2010

Strawberry Girl by Lois Lenski

Few people realize how new Florida is, or that, aside from the early Indian and Spanish settlements, Florida has grown up in the course of a single man's lifetime.

"She's got our markin' brand on her, Pa. A big S inside a circle," said Essie.

The man, Sam Slater, looked up. "Shore 'nough, so she has."

"She's headin' right for them orange trees, Pa," said Essie.

"Them new leaves taste mighty good, I reckon," replied her father. "She's hungry, pore thing!"

A clatter of dishes sounded from within the house and a baby began to cry.

"You'd be pore, too, did you never git nothin' to eat," said the unseen Mrs. Slater.

There was no answer.

Wednesday, September 29, 2010

Ginger Pye

Tuesday, September 21, 2010

It's Been So Long Since Anyone's Posted!

I've been reading and writing a lot for a job, and haven't had much time for reading for pleasure. The job wraps up in October, though, so I will definitely finish Roll of Thunder, Hear My Cry and Dicey's Song and the eight or so other Newbery winners I still haven't read yet at some point after that.

Meanwhile, here's an issue that has come up frequently here (and specifically mentions Dr. Dolittle):

What to Do About Classic Children's Books That Are Racist

And if you're interested in getting a jump on the Newbery winner for 2010 (my vote is already cast for A Conspiracy of Kings, whether it's the best choice or not. I love that series so much I can't be an impartial judge), the Heavy Medal blog is up and running again.

Boy, it is really annoying that when you Google "Heavy Medal Newbery" they automatically switch your search term to "heavy metal Newbery".

Thursday, May 6, 2010

Caddie Woodlawn, by Carol Ryrie Brink

I did love this book during my tween years, and now rereading it as an adult, all I can think of is how very much like the Little House books it is. But this story takes place at least 15 years before Laura Ingalls Wilder's birth. And interestingly enough, I counted at least two stories in this book that I also remember having read in the Little House series. I think perhaps they simply became Wisconsin urban legend. I did my google maps homework and found that Laura was born less than 40 miles from where this book takes place, which explains the common themes- Caddie Woodlawn is based on the true story of the author's grandmother.

Caddie takes place during the Civil War. Caddie's father, who runs the local mill, is affluent enough that he was able to pay to have a man sent in his place. The family also has hired men living full-time on the property. Caddie is the middle child of five. There used to be six, however, when the family moved west from Boston the youngest girl, Mary, was ill and died. Because Caddie was weak and sickly also, Mr. Woodlawn convinced his wife to allow her to run wild with the boys to regain her health, convinced that she would take up more feminine behavior when she became ready.

In addition to their own small family, the Woodlawns are on very good terms with the Indians that live locally, especially Indian John (who has the advantage of command of the English language, although it's unfortunately depicted as the stereotypical pidgin English common in books from this period). The book follows a year in Caddie's life- picking nuts, riding horses, going to school, and worrying about rumors of Indian massacre, eagerly awaiting the mail after a long winter, and eating entirely too much turkey. Over the course of events, Caddie does mature and become ready to at least consider that a lady's skills have some merit.

Also impressive for the time the book was written in is the way the Woodlawn family is scornful of a man in the community who had taken an Indian wife in the days when the town was not yet settled. Not because he took an Indian wife, but because he is clearly ashamed of her and their three children, and because he sends his wife away to rejoin her people when rumors of massacre have made her uncomfortable to keep. Stereotypes notwithstanding, it's a perspective that you don't often see represented. As their mother tells the Woodlawn children, "Sam Hankinson hasn't a very strong character. Now if your father had married an Indian. . . you may be sure that he would never have sent her off because he was ashamed of her."

I did love my paperback copy of this book with Trina Schart Hyman illustrations; they have so much more character than the airbrushed bland ones that are in the 1958 edition I borrowed from my library this week (see right). Who makes a better-looking tomboy, I ask you?

Cross-posted from http://oldnewberries.blogspot.com/ in which Melanie and Sue have made it a personal mission to read all Newbery Award and Honor books.

Wednesday, April 21, 2010

Island of the Blue Dolphins

I remember when my children read Island of the Blue Dolphins by Scott O'Dell. It was many years ago but I still remember that my daughter cried while my oldest son tried not to cry. So I remember it as a sad book because a dog dies.

I remember when my children read Island of the Blue Dolphins by Scott O'Dell. It was many years ago but I still remember that my daughter cried while my oldest son tried not to cry. So I remember it as a sad book because a dog dies.It is much more than that. This book was awarded the Newbery Medal in 1961. I was only eight years old and I wonder why (or if) I did not read the book. This was published in a time of women's liberation in the United States. I don't know that I would say that liberation is what this book is about, but certainly Karana moved outside female cultural roles as she survived alone on an island off the coast of California.

The book is based on the life of a real woman who lived alone on the island of San Nicolas from 1835 to 1853. She was named Juana Maria by a priest who was with her when she died only seven weeks after she was rescued by George Nidever. She is buried at the Santa Barbara Mission in California. To learn more, click HERE.

In Island of the Blue Dolphins, our heroine Karana stays behind on her island after the Aleuts killed many of the men of her tribe and the others had left on a large ship. She stayed because she could not find her brother on the ship. After her brother's traumatic death, Karana lives alone on the island. O'Dell uses imagery to help the reader visualize how Karana takes care of herself and the island. A strong girl, Karana does what she must do to survive. In the end, she has experienced joy and sorrow on the island. I liked the story and feel the students would as well.

TITLE: Island of the Blue Dolphins

AUTHOR: Scott O'Dell

COPYRIGHT: 2006

PAGES: 184

TYPE: fiction

RECOMMEND: I would recommend this to Middle School children who are naturalists (no matter what your definition) or for girls who need to learn that they can do anything they wish to do.

Sunday, April 4, 2010

Shen of the Sea by Arthur Bowie Chrisman

Shen of the Sea: Chinese Stories for Children by Arthur Bowie Chrisman. illustrated by Else Hasselriis

Shen of the Sea: Chinese Stories for Children by Arthur Bowie Chrisman. illustrated by Else HasselriisPages: 221 pages

Ages: 8+

Finished: Mar. 31, 2010

First Published: 1925

Publisher: E.P. Dutton

Genre: short stories, folktales

Rating: 4.5/5

First sentence:

"A shamelessly rainy day, my honorable Brother Chi."

Acquired: Bought and own a copy.

Reason for Reading: Read aloud to my 9yo son. We always have a book of folktales, fairy tales, myths, etc. on the go, reading one story every school day.

Comments: I have read this book once before to myself some time ago, as an adult, and came away with the impression that it was OK (maybe 3 stars) but now I think I've found out the problem with that first reading. This book is meant to be read aloud! The stories are told in a storyteller voice that just rolls off the tongue when reading out loud and brings them gloriously to life. The stories are hilarious and I can't say that my ds or I didn't like even a single one the tales. I'm not convinced these are traditional Chinese stories (I've read a lot of folktales in my life and never heard any of these before) but would guess that Chrisman wrote them himself based on the style of Chinese tales. The tales often rely on repetition, some are origin stories and they cover a wide spectrum of characters from peasants to princesses and Kings. A number of the stories are about someone who is not too bright or is incredibly lazy or stubborn. While the great majority of tales are folktales a few pass over into fairytale territory with the appearance of a few dragons and other Chinese mythical creatures. Every single time this book came out my son's face lit up, he thoroughly enjoyed it! I also had a ton of fun reading it. This book has a habit of getting mixed reviews and to those who give it low ratings, I ask you to read aloud a couple of stories to a child or group of children. Then see if you don't change your mind! I've found in my 21 years as a mother that some children's books just beg to be read aloud and don't do the trick when read silently. The only thing I'm not too keen on are the silhouette illustrations. Yes, they add to the ethnicity of the book but detailed drawings would have been more fun to look at.

Saturday, March 13, 2010

2010 When You Reach Me

When You Reach Me by Rebecca Stead is a fascinating novel with a number of story lines. While I enjoyed the book (and stayed up until 12:30 in the morning to finish it, which speaks volumes), I wonder if the seconday story lines will be understood by young readers who might not have previous knowledge to support full interest. Certainly it appealed to the Newbery panel!

When You Reach Me by Rebecca Stead is a fascinating novel with a number of story lines. While I enjoyed the book (and stayed up until 12:30 in the morning to finish it, which speaks volumes), I wonder if the seconday story lines will be understood by young readers who might not have previous knowledge to support full interest. Certainly it appealed to the Newbery panel!The novel takes place in 1979 and is narrated by twelve year old Miranda, who lives with her mother. Miranda experiences the pains of growing up while a mystery surrounds her. Miranda's mother is excited about being on the $20,000 Pyramid, a television game show which was popular in the 1970s. Along with her mother's boyfriend, the family helps the mother practice for the show. This story line might be an unknown for young people today.

Another story line, which is at the heart of the mystery, focuses on Madeline L'Engel's book A Wrinkle in Time and the idea of time travel. Marcus, who becomes a friend to Miranda, has theories on time and space. If one were unfamiliar with L'Engel's book, perhaps this story line might also have some gaps. Of course the simple answer to this problem is to read L'Engel's classic book and start over.

I liked this book. I didn't love it. The writing and tone were good and I wanted to get to the bottom of the mysterious notes. Overall, When You Reach Me should hold broad appeal for the age range Grade 5-8, which is where we have placed the book in our collection at the library.

TITLE: When You Reach Me

Monday, March 1, 2010

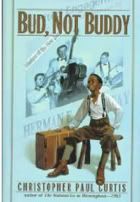

Bud, Not Buddy by Christopher Paul Curtis

Bud, Not Buddy

by Christopher Paul Curtis

This book won the 2000 Newbery Medal for "the most distinguished contribution to American literature for children" and the award is well-deserved.

Set in Flint and Grand Rapids Michigan in 1936, the story covers three tumultuous days in the life of Bud Caldwell, orphan, age 10. Bud's single mom died when he was six and he has lived in the orphanage and various foster homes since. Bud's already wise to the system. So wise that he can feel sorry for the six-year-old who's being sent to a foster home in the most recent "deployment" from the orphange.

...Six is a real tough age to be at. Most folks think you start to be a real adult when you're fifteen or sixteen years old, but that's not true, it really starts when you're around six.

It's at six that grown folks don't think you're a cute little kid anymore, they talk to you and expect you to understand everything they mean. And you'd best understand too, if you aren't looking for some real trouble, 'cause it's around six that grown folks stop giving you little swats and taps and jump clean up to giving you slugs that'll knock you right down and have you seeing stars in the middle of the day. The first foster home I was in taught me that real quick.

(If that doesn't break your heart, what will?) To cope with his world in which children must be "too wise, too soon", and can't trust any adult, Bud has composed "Bud Caldwell's Rules and Things for Having a Funner Life and Making a Better Liar Out of Yourself". Sprinkled randomly throughout the book (#3, #63, #29, #16 etc), they're a melange of timeless childhood advice, hilarious reasoning, and poignant realizations.

Bud's busting out of the padlocked shed his newest foster parents have locked him in, and he's off to find his unknown father. When she died, his mother left a half-dozen small stones inscribed with letters and numbers, and five different flyers for the jazz band Herman E. Calloway and the Dusky Devastators. Bud is convinced that Herman E. Calloway is his father.

This is a young adult book that will be enjoyed by adults and adolescents alike. Bright and polite Bud narrates his own story and, although he relates the precarious position of an orphan during the Great Depression, he never sounds like he feels sorry for himself. Life is full of unpleasant situations but with his self-authored book of "Rules and Things...", he can find a way to deal with anything. You'll be uplifted by his story.

I rate Bud, Not Buddy

Friday, February 26, 2010

2010 - When you Reach Me

I just finished reading When You Reach Me, by Rebecca Stead. It won the Newbery award this year, so I figured it would be worth reading.

I found the book rather disappointing. In the last few pages, all of the bizarre and confusing things that happened through the book are all explained, and everything falls in place but the fact is that until that moment, the book is hard work to get through. I think it's unlikely that my kids, anyway, would persist through to that Ahah! moment, and so would dismiss the book with their usual designation of "boring."

Added to that, the book relies heavily on the reader being familiar with "A Wrinkle in Time", a book which (yes, I know, it's heresy) I can't stand. So, if you're familiar with Wrinkle, and if you liked it, perhaps this will resonate with you. But it really didn't work much for me.

Thursday, February 11, 2010

Some Great Reviews and Links on Newbery Winners

Wednesday, February 3, 2010

Crispin: The Cross of Lead, by Avi, 2003

Recently I read Avi’s Newbery winning young adult novel, Crispin: The Cross of Lead. My initial opinion was that it was extremely well-written. I was especially enamored of Avi's descriptions of life in and around a tiny medieval English village. The death and burial of Crispin’s mother, Asta, set the scene for traumatizing upheavals in young Crispin’s life. Before long he was an outcast, his home burnt, his name dishonored. A false accusation sent him running into the woods for safety.

Crispin’s sole possession, a cross of lead, was a common one at that time. His mother wrote something on it but since he had no education, he couldn’t read it. At the age of thirteen, a rather young age for the main character in a young adult novel, Crispin set out as a fugitive to make a life of his own.

Though thirteen is young for the main character in a young adult novel, Crispin: The Cross of Lead should not be classified as middle grade, in my opinion, because of the subject matter, which includes violence. My library has it labeled 'young adult'. Perhaps Avi chose this young age for Crispin because this is intended to be the start of a trilogy, and during subsequent novels he will be growing older.

Toward the end of the novel there were a few events that I couldn’t believe Crispin could be capable of. My suspension of disbelief wavered. I was also distressed by his tendency to disobey -- something that normally would get a child in a lot of trouble! Instead Crispin managed to be a hero each time his disobedience surfaced. This annoyed me, yet I was happy that he wasn’t destroyed by the enemy and that he lived to disobey again.

Compared to other medieval age historical novels on the Newbery list, I thought this one to be one the best. Others I’ve read include The Door in the Wall, which bored me, and Adam of the Road, which is sweet but simplistic compared to today's standards.

Avi’s story-writing talents are well-developed and current. As I’m also a writer of middle grade and young adult novels I cannot help but spot anything that’s not on the current PC list for writers. Older Newbery Medal winners sometimes make me shake my head thinking, “If that book was written now it would never get published,” because it breaks the rules that I, as a modern writer, must live with. Avi’s books, of course are cream of the crop... a good source of novels we more modern writers can learn from.

Crispin: The Cross of Lead kept my interest and did not disappoint. I loved reading it! I also liked Avi's novel, The True Confessions of Charlotte Doyle, which was named a Newbery Honor Book in 1991.

My book review blog: Linda Jo Martin.

My children's literature blog: Literature For Kids.

Sunday, January 24, 2010

Young Fu of the Upper Yangtze

You know, a fair number of adults today seem to enjoy Young Fu of the Upper Yangtze, by Elizabeth Foreman Lewis. A couple of my friends have said positive things about it, and it's got an average rating of 3.56 on goodreads.com, which gives it more stars than 1/3 of the other Newbery prize winners. The Allen County Newbery Book Discussion Group even rated it relatively high (at 61 out of 88).

You know, a fair number of adults today seem to enjoy Young Fu of the Upper Yangtze, by Elizabeth Foreman Lewis. A couple of my friends have said positive things about it, and it's got an average rating of 3.56 on goodreads.com, which gives it more stars than 1/3 of the other Newbery prize winners. The Allen County Newbery Book Discussion Group even rated it relatively high (at 61 out of 88).I can't figure them out. I liked Secret of the Andes more than Young Fu! Heck, I actually had more fun reading Dobry. And it's not that I don't like reading about historic China. I liked The Good Earth when I read it in high school, and I liked it even more when I read it again a couple of years ago (interestingly, Pearl S. Buck wrote an introduction to Young Fu of the Upper Yangtze for the 1973 edition that I checked out of the library).

Unfortunately, unlike the characters in The Good Earth (which won the Pulitzer Prize 1932, the year before Young Fu won the Newbery...hmmm, is there a connection?), I found the characters in Young Fu of the Upper Yangtze rather uninspired. Downright boring, in fact. I kept waiting for Young Fu to do something exciting, but even his minor transgressions were disappointing to me (unlike Johnny Tremain, for instance, another Newbery-winning apprentice whose flaws kept me reading).

I thought Scholar Wang was going to be an important character in his own right (especially as he appears in the first chapter), but he seems to exist mainly to embody "Classic Wisdom" (p. 10), to provide the means for Young Fu to learn to read and write, and for Young Fu to be able to show appreciation for the elderly and to display compassion when Scholar Wang is sick.

The women in Young Fu are even more disappointing. Fu Be Be, Young Fu's mother, is portrayed as rather stingy, short-sighted, and superstitious, and there really aren't any other important female characters in the book. The idea that men in Chungking (modern Chongqing) considered women to be foolish, emotional, and weak is often mentioned, and although it is clear (I hope!) that this is an historic cultural perspective, it is unfortunate that this idea is not countered by a single remotely sympathetic female character - with the possible exception of a blond foreign doctor (or possibly a nurse). I don't think it's true that girls don't enjoy boy's coming-of-age stories, but I don't think that too many girls today would enjoy this one. And it is just discouraging to keep reading about women's roles in this society without ever hearing their voices, like you do in The Good Earth.

Girls always cried during the tedious moons of foot binding. He had seen them often enough in the village, though a few of the farm women kept their daughters' feet of natural size that they might help in the fields. But this was not common. Everyone agreed that it was better to stand the agony of foot binding than the stigma of possessing large feet. And even though deformed feet permitted a woman to work only around the house, they were important in getting a husband.....He, Young Fu, was glad that his mother's feet were small; that she was not a coolie woman was plain for all to see (p. 39).I didn't mind reading about the mechanics of making brass (although Young Fu is apprenticed to a coppersmith, the story revolves around brass), and of the selling of pots, kettles, braziers, and trays, but I thought Lewis was at her most interesting when she was describing the city of Chungking itself. The city streets, steaming paving stones, shops, the tenement in Chair-Makers' Way, and the soldiers, political activists in the tea shops, and the deadly flood - I thought that all of these things were much more interesting than hardworking, virtuous Fu Yuin-fah. But I really want more than a travelogue and history when I'm reading historic fiction; I want interesting characters and a compelling plot, too!

The chapters in Young Fu are rather disjointed - each chapter reads like a separate story, which works well for some books (like The Graveyard Book, for instance), but didn't help keep my flagging interest in Young Fu's story. Lewis' frequent use of proverbs annoyed me, too, even when I agreed with the sentiments. They just seemed a bit trite and forced to me:

The story (in my edition, anyway) concludes with ten pages of Notes by Alison R. Lanier, updating readers on some of the technological and political changes that have taken place between Young Fu's original publication in 1932 and the printing of the new edition in 1973. Since almost as long a timespan has passed since the Notes were written ("Planes reach almost any part of China the same day. Many of the planes are British turbo-jets; others are of Russian make", p. 259), with some pretty major changes occurring in China, I think it's time for an update of the update.

Laziness never filled a rice bowl (p. 16).

At birth, men are by nature good of heart (p. 54).

Character is made by rising above one's misfortunes (p. 149...doesn't this contradict the previous one?).

He who rides on a tiger cannot dismount (p. 180).

Medicines are bitter in the mouth, but they cure sickness (p. 197).

Wednesday, January 13, 2010

The 2010 Newbery Winner Will be Announced...

...next Monday, January 18.

I've read some of the contenders already:

When You Reach Me, by Rebecca Stead

The Evolution of Calpurnia Tate, by Jacqueline Kelly

The Dunderheads, by Paul Fleischman

Charles and Emma: The Darwins' Leap of Faith, by Deborah Heiligman

Anything But Typical, by Nora Raleigh Baskin

Written in Bone, by Sally Walker

Catching Fire, by Suzanne Collins

Season of Gifts, by Richard Peck

and I'm on the library wait list for Where the Mountain Meets the Moon, by Grace Lin, and Claudette Colvin, by Phillip Hoose. From reading at the School Library Journal's Heavy Medal blog, I think that Stead, Lin, and Hoose are the front runners. But I know that the both the critics' and popular favorites are quite often not chosen. Tune in next week for the results.

Dobry

Well, I didn't really hate Dobry, by Monica Shannon, but then again I didn't have very high expectations for this 1935 winner.

Well, I didn't really hate Dobry, by Monica Shannon, but then again I didn't have very high expectations for this 1935 winner.I liked reading about the round of seasonal chores in a Bulgarian village. A lot of the story reminded me of an old-fashioned ethnography, with its dispassionate depictions of the peasants plowing, planting, hoping for rain, taking their cows to mountain pastures, harvesting tomatoes and peppers, winnowing wheat, and making bread (note the hanging peppers and the bread and oven on the cover). There were some mildly interesting and exotic words to ponder, and a few nice descriptions of food:

Roda served cherry sladco to all her guests. They sat on three-legged stools around the jamal fire which had only new air to warm up because the windows looking onto the village street were open to let the music of rain and the smell of rain come into the room. Grandfather brought in a tubful of red peppers at a time and got out a jug of sauerkraut juice from a cubby-hole back of the jamal. Peppers went on strings so fast that he could do nothing at all except serve his guests and refill the pepper tub (p. 35).I think sladco is some kind of sweet, but it's not listed in my food dictionary or the Oxford English Dictionary, and when I Google sladco I get a thousand hits for a Russian candy company. A jamal is apparently some kind of clay fireplace stove (again, too many hits, given its popularity as a first name). I also liked the spelling of "bowlder" for boulder, the Wickerwockoffs, the descriptions of the tunnels through the snow in the village in the winter, and some of the Christmas and New Year's traditions that Shannon describes, although at times it seems like she's trying to load as many extraneous facts about Bulgarian culture as she can onto poor Dobry's shoulders.

The "massaging Gypsy bear" - first mentioned on the second page, and then appearing periodically - is just bizarre. Did such a thing really exist? Did this bear not have claws? Was it really that exciting to have a bear walk on your back? It's a little hard to believe that this gave "every peasant man in the village" something that "wiped out all thought of his summer toil and gave him the feeling that a long vacation gives to other men (p. 93)".

I don't know if the gypsy bear was stranger than when Dobry envies the older men in the village who have icicles on their chest hair in the winter. When Dobry says "I'll be proud the day I can stride in here, clinking at the chest. It's a noise I love even better than the noise of sledge bells on our oxen (p. 131)", all I could do was goggle at the page in disbelief. And then there's the idea that if you sneak a piece of pig's skin to munch on at night from the slaughtered animal hanging in your house, the ghost of the pig will ride on your back. But these passages did keep me from being bored, as I was with some of the other Newbery winning exaltations of "simple" cultures (see Secret of the Andes and ...And Now, Miguel, for instance).

But what happened to Dobry's father? He must have died sometime after Dobry was born (there's a story about him on the day of Dobry's birth), but no one seems to mourn him, not even Dobry's mother, Roda. Then again, it was hard to care much about any of the characters in the book, given the way they are portrayed. Dobry is interested in art instead of farming, but this big conflict in his life isn't even mentioned until page 80 (of a 176 page book). He's really just a generic happy Bulgarian peasant boy and his mother is a hardworking farm wife. Dobry's grandfather is a hearty man who is most notable for the number of things he is able to keep in the sash belted around his waist (on page 46, this includes "two loaves of bread, a goat cheese, garlic, and his tall wooden salt-and-paprika box," along with six tomatoes!), and of course his ability to melt snow with his body heat.

I really didn't like the illustrations by Atanas Katchamakoff (including the original cover), and agreed with Alicia's comments on them. I didn't like the stories that Grandfather told in the book, either - I think my least favorite was the story of Hadutzi-Dare and the Black Arab. I did wonder why the illustration for this story was listed in the front of the book as "Heidout-Sider Pulling the Water Buffalo with a Chain" (are Hadutzi-Dare and Heidout-Sider different translations of the same hero?), but not enough to research it after a cursory Google didn't enlighten me. I also didn't like the fact that the chapters are neither titled nor numbered, and that the only way you can tell it's a new chapter is by the fact that there's an illustration on the upper third of the page.

I didn't much care for Shannon's descriptions of Dobry's art, either:

Only youth could have brought the freshness Dobry brought to his Nativity, and only a primitive genius, Indian or a peasant like Dobry, could have modeled these figures with strength, assurance, sincerity - untaught in any school (p. 146).I would be very surprised to hear that any kids today care for this book.